What Carroll refers to as “Red Magic” or “War Magic” is generally considered to be magical techniques used for magical combat of some sort, such as ‘cursing’ one’s enemies or protecting oneself against such things by said enemies. I’ve written some about Magical protection, but rarely touched on the topic of the more offensive side of things.

Before delving too deeply into this, I want to say that, while there are certainly times when justice, retribution, and vengeance are necessary and there are definitely a myriad of valid reasons to be skilled in magical protection, if you find yourself constantly engaged in occult battles there are very likely other areas of your life that need to be looked into. You might be walking in the same circles as assholes, or you may be one. I’ve personally found myself in both of those particular situations.

In a lot of ways, I view Red Magic, especially the offensive variety, kind of like a home security system, car insurance, or learning martial arts. It’s a good thing to have in your toolbox, but it’s better if you never need to use it. Some people in the modern occult world have issues with the idea of cursing and combative-type Magic, and that’s reasonable enough, but I’m not one of those people and it’s certainly an aspect of many traditions. I do try to keep such things firmly in a ‘what you deserve’ perspective, however. No more and no less.

Cursing, or the casting of malevolent spells, and ways of protecting against them or returning them to their sender, are as ancient as magic itself. Though modern views often cast these things as mere superstition, for many cultures, these acts remain deeply symbolic and, at times, feared.

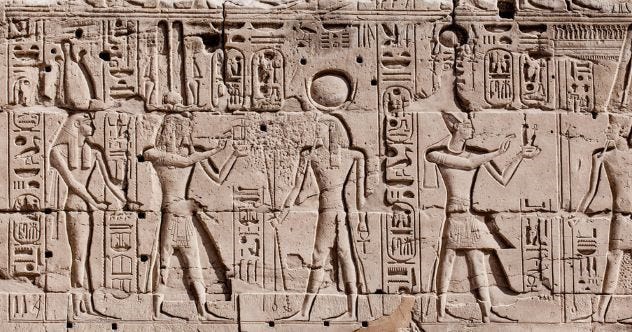

The ancient Egyptians used cursing as a tool for justice and retribution. Their practice included inscribing the names of enemies onto clay, wax, or pottery, accompanied by elaborate curses intended to strip away power and divine protection, which were then ritually destroyed or buried to bring harm in both spiritual and physical realms. Tomb curses, etched by pharaohs and builders, invoked divine wrath against violators, threatening disease, misfortune, or death to protect the sanctity of the dead. These practices reflected the Egyptians’ conviction that words and ritual actions could tangibly shape fate, serve as spiritual deterrents, and safeguard both the living and the deceased from harm or desecration.

Later, the Greeks and Romans used curses, too, for justice, vengeance, or love through magical means. In ancient Greece and Rome, the casting of curses—known as “katadesmoi” in Greek and “defixiones” in Latin—formed a vivid thread in the cultural fabric of daily life. These societies viewed magic as a practical means of influencing fate, seeking advantage in love, litigation, commerce, or competition. Practitioners would inscribe spells onto thin sheets of lead, carefully naming their intended targets and the specific misfortunes they wished to invoke, such as the binding of an opponent’s tongue in court or the separation of lovers. These tablets were often deposited in graves, wells, or sacred sites, believed to enlist the intervention of chthonic spirits or deities of the underworld who would carry out the curse. Beyond mere personal rivalry, such acts reflected a belief that the supernatural could be harnessed to regulate justice, redress grievances, or even sway the favor of the gods—blurring the boundary between religion, law, and magic in the classical world.

Medieval and early modern Europe teemed with stories of witches and cunning folk, some revered, some feared. Cursing, or ‘hexing,’ was both feared and, in some cases, sought after for protection or revenge. Hexing took on countless forms, echoing both the anxieties and ingenuity of the age. The so-called “hex” was not merely a whispered threat, but a sophisticated act rooted in oral tradition, ritual, and symbolism. Hexes might be cast with incantations spoken in forgotten dialects, or through the careful preparation of poppets—small figures fashioned from wax, clay, or cloth—infused with bits of the intended victim’s hair, nail clippings, or scraps of clothing. Some practitioners would bury these effigies at liminal spaces such as crossroads or within the victim’s property, believing that supernatural forces, once invoked, would take hold. The line between curse and protection was often thin: a single verse or gesture could, depending on intent, either shield a household or blight a rival’s fortune. Such practices endured not only because of their perceived efficacy, but because they resonated with a society where the boundaries between the natural and supernatural were ever porous, and where the unseen—whether blessing or bane—was woven into the fabric of daily life.

Witch bottles have a storied place in the history of European folk magic, particularly in the British Isles from the sixteenth century onward. Originally conceived as protective devices, these bottles were often filled with a curious assortment of items—rusty nails, pins, hair, nail clippings, and sometimes bodily fluids such as urine—each chosen for its symbolic association with the intended target or the nature of the harm to be averted. The bottle would then be sealed and buried beneath the threshold of a home, within a hearth, or hidden in the property’s boundaries, where it was believed to trap, repel, or neutralize malicious magic aimed at the household or individual. While most accounts emphasize their use as apotropaic charms against witchcraft, some records suggest that witch bottles could also serve as tools of maleficium, designed to send harm back to a perceived aggressor. Their persistent presence in archaeological finds attests to the deep-rooted anxieties around supernatural threats in early modern Europe, as well as to the resourcefulness with which people engaged the unseen world in hopes of securing safety and justice.

African spiritual traditions brought to the Americas, such as Hoodoo and Obeah, have preserved potent cursing practices that serve as tools of spiritual justice and personal empowerment. In Hoodoo, cursing—exemplified by the use of "Hot Foot" powder, a blend of red pepper, sulfur, and graveyard dirt—acts not out of malice, but to restore balance and protect community, used only when all other options are exhausted. Similarly, Obeah practitioners in the Caribbean invoke ancestral spirits to "shadow" wrongdoers with illness or misfortune, typically in response to violations of trust or communal norms. Both traditions emphasize that curses are not arbitrary acts of vengeance, but means of reasserting justice and restoring spiritual equilibrium when conventional avenues prove inadequate.

One of the most enduring and widespread forms of belief in malignant supernatural influence is the Evil Eye, a concept that has manifested across civilizations from antiquity to the present day. Tracing its origins to ancient Mesopotamia and classical Greece, the Evil Eye is rooted in the idea that envy or malice, whether intentional or unconscious, can be transmitted through a mere glance—causing illness, misfortune, or even death. Amulets, talismans, and protective gestures developed alongside the belief, with the iconic blue-and-white nazar bead of the Mediterranean and Middle East standing as a recognizable countermeasure. In the Roman world, mosaic eyes adorned thresholds, while in South Asia, black threads or symbolic marks shielded the vulnerable from harm. Despite regional variations in practice and symbolism, the underlying conviction in the power of a hostile gaze to disrupt the fabric of daily life persists, weaving its way through folk customs, religious rituals, and social interactions around the globe.

Repelling the Evil Eye has long been a matter of both ritual and daily custom, reflecting humanity’s persistent desire to shield themselves from unseen malice. Across the Mediterranean and beyond, amulets such as the iconic blue-and-white nazar bead, hamsa hands, or even simple knots of red thread are worn or displayed to deflect envious glances and absorb the harmful energy they might carry. Incantations, blessings, and ritual gestures—like spitting three times or making a discreet hand sign—are invoked at moments of perceived vulnerability, especially during major life events or displays of good fortune. In some traditions, protective herbs like rue or garlic are hung above doorways, while in others, salt is scattered or water is sprinkled to cleanse spaces of lingering negativity. Regardless of the method, these acts are unified by their intent: to intercept the hostile force before it can manifest, transforming it or sending it harmlessly back to its source, and in doing so, to guard not only the individual but the harmony of home and community.

Today, War Magic continues to evolve. Modern magicians may draw from traditional or eclectic sources, adapting techniques for new contexts. If you wander around the internet you might find that modern baneful magic includes some interesting ideas.

Mirror box spells, a contemporary evolution of sympathetic magic, involve placing a representation of the target—often a photograph, a personal item, or a poppet—inside a box lined with mirrors on all sides. The practitioner may add herbs, pins, or written intentions as dictated by their tradition or personal style. The central concept is reflection and entrapment: the mirrors are believed to bounce the target’s negative energy, hostile behavior, or malicious intent endlessly back upon themselves, effectively turning the force of the curse inward. The box is typically sealed and hidden away, sometimes buried or stored in a dark, undisturbed place, with the intention that the unwanted actions or influences of the target become contained, neutralized, or redirected.

Freezer spells, on the other hand, draw on the elemental symbolism of ice and stasis. In this practice, the practitioner writes the name of the person to be “frozen,” often accompanied by a description of their negative behavior or a specific petition (such as “stop gossiping about me”). This paper is then sealed—sometimes in water, vinegar, or another symbolic liquid—inside a container and placed in the freezer. The act of freezing is believed to halt the target’s harmful actions, slow down their influence, or otherwise "put them on ice," rendering them powerless to continue causing harm. Some spell-casters include additional ingredients, such as hot peppers to “burn” the person’s tongue or alum to “shut their mouth,” layering intent upon intent.